I have long been fascinated by the fact that the majority of information that we have about ancient societies from around the world comes from the study of their art.

Fortunately for us, art somehow, and at times miraculously, manages to survive. War, pillaging, earthquakes, tsunamis, plague, famine, volcanoes all seem no more troublesome than an annoying visit from a fly at a picnic to art. A simply wave of the hand, or perhaps in the case, the brush, is all that is needed to swat away the pesky intruder.

While humanity may vanish, fall, or be displaced, art seems to remain steadfast and true quietly and patiently waiting in airless tombs, beneath mountains of rubble, or on the walls of an undiscovered caves waiting to reenter the spotlight. A bit worn around the edges certainly, but, once carefully cleaned, restored and studied, it becomes a treasure trove of information sparkling with wisdom like the twinkling of a distant star.

Taking the historic dimensions of art into account, it was with great pleasure that I came across Steve Cohen’s article, "The Gross Clinic Restored" in the latest issue of the The Broad Street Review. Of course, the article references the 1875 masterpiece painted by the fascinating, and at the time controversial, Thomas Eakins.

(Thomas Eakins Carrying a Woman, 1885. Photograph, circle of Eakins.)

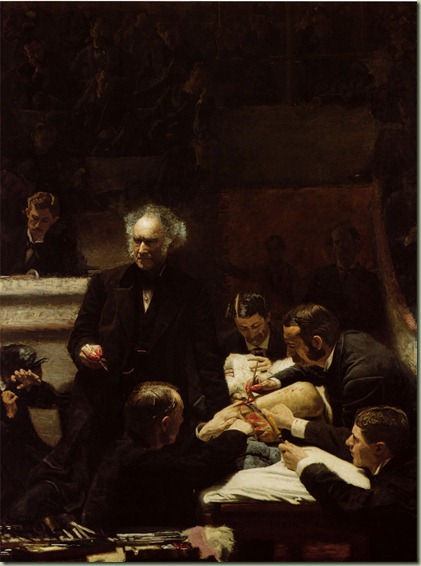

The amazing work which has been restored and is now on display through January 9, 2011 at the Pearlman Building, Philadelphia Museum of Art (Ben Franklin Parkway and 26th St. (215) 763-8100 or www.philamuseum.org) and after January 9, 2011 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (Broad and Cherry Sts. www.pafa.org) is described in Wikipedia’s entry as having “an important place documenting the history of medicine—both because it honors the emergence of surgery as a healing profession (previously, surgery was associated primarily with amputation), and because it shows us what the surgical theater looked like in the nineteenth century.”

Beyond the painting’s undeniable historic significance, the work itself is masterfully executed (a detailed version maybe found online here). The composition, the muted sunlight filtered through an overhead skylight (at that time, surgery was only scheduled between 11 A.M. and 2 P.M., when the sun was high), the flowing blood and open cut, the expressions of those involved in the surgery and those watching and taking notes, the shadowed figures (including one woman anxiously hanging onto a wall for support) in the background – all work in unison to create a truly astounding work of art.

In case the historic significance of the work is lost on you initially, Cohen also wisely mentions in his article that a “fascinating contrast is seen in The Agnew Clinic, which Eakins created 14 years later. That painting chronicles the use of electric lights, the presence of a female assisting the surgeon, and white gowns and sterilized instruments in a covered case”. What a difference 14 years make, eh?

What I personally take from the work is my own bit of history. As a young child, this painting absolutely fascinated me when I came across it in the yellowed pages of an ancient set of encyclopedias that had been passed down from my grandfather. It wasn’t the story that was being documented that fascinated me, it was the work of art itself. I can honestly say that this was among a handful of works that inspired me to live my life making art. As a child, I somehow knew instinctively that this was a monumental work of art at the the person who created it must have been very gifted indeed. Eakins managed to become the equivalent of an artistic superman to me - one of many over the years, but certainly of of the first.

Childhood art fantasies aside, one of the most beautiful aspects of art is that fact that an artist never knows initially whom may be inspired by it, or , in context of this blog entry, what its historic impact may be years down the road.

As Hippocrates once said - “Ars longa, vita brevis”. Art is long, life is short. . .

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment